At work, trust is often framed as a simple question: will this person do their job as is expected of them? “I trust Ari to track his hours accurately,” or “I trust Melinda to do her part of the group assignment.”

This definition of trust is purely transactional: I’ll do my job if you do yours. But in teams where trust has been violated, the emotional turmoil that’s often present—think of two team members who no longer want to be in the same room, let alone on the same team, or scar tissue that makes it impossible for a team to believe in a new leader’s intentions—suggests that there’s more to trust than a simple exchange of outputs and behaviors.

A more accurate definition of trust is that it’s the decision to make ourselves vulnerable to others: who can we rely on? How much are we willing to risk getting hurt? From collaborating to get your work done, to relying on leaders for your very livelihood, we need to be able to trust those whom we work with. In other words, if you work on a team, you must accept and navigate some level of vulnerability.

If trust sounds a lot like psychological safety, it’s because (according to Amy Edmonson) trust is a significant antecedent to psychological safety. Without trust, psychological safety is impossible. Moreover, while psychological safety is a belief about the group’s collective norms, trust is a choice between two individuals, which is determined by two things: the trustor’s propensity to trust, and the trustee’s overall trustworthiness.

What makes people willing to trust others?

Our personal willingness to trust—to make ourselves vulnerable, to literally give others power over ourselves—is influenced by several factors:

First, trust is individual. Our societies, our families of origin, our formative years, and our exposure to other cultures all play important roles in how we decide who, when, and to what extent we trust. As a result, we must remain self-aware of how past experiences shape our willingness to extend our vulnerability in the present.

Second, trust is social. We have an easier time trusting people like us, so in new teams, we tend to fall back on stereotypes (gender, age, race, etc.) to determine if someone shares one of our identities. We must fight to overcome biases that prevent us from recognizing others’ trustworthiness.

Third, trust is contextual. The environment influences the level of difficulty for trust. For instance, trusting someone new can feel riskier if we’ve only worked with them through Zoom, while we might feel more comfortable trusting others if we join what we perceive as a stable and successful existing team. We must be aware of how our environment is shaping our choices.

Fourth, trust is temporal. Trust takes time to earn and flourish. Teams often proceed through a series of stages, moving from transactional forms of trust to a closer alignment of vision, goals, and values as they gain one another’s trust. We should reflect on how our feelings about trust change over time with our teams, and recognize when and how trust has improved.

How can I help others to trust me?

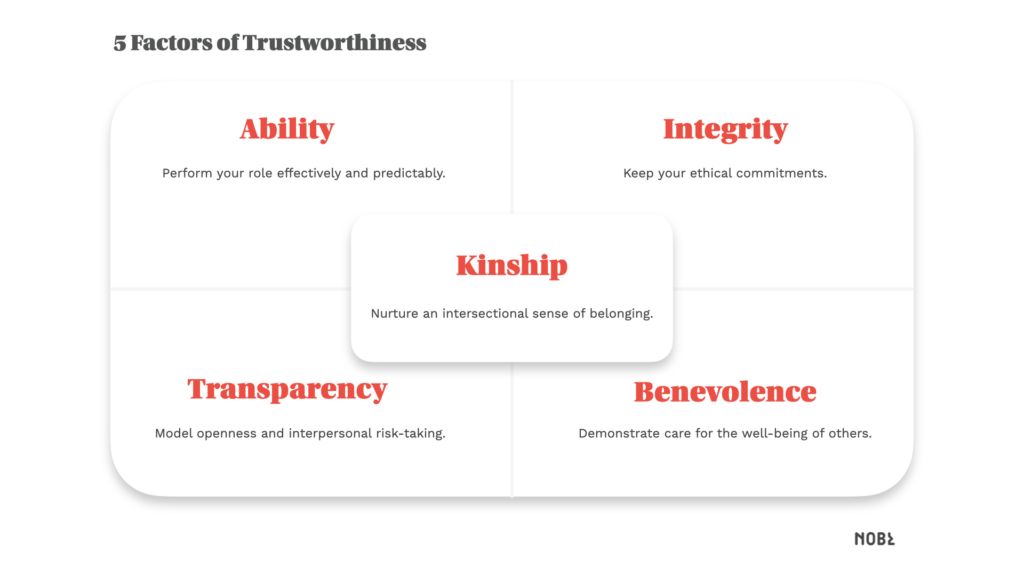

Again, trust requires two factors: someone willing to trust, and someone who is worthy of that trust. To truly foster trust with peers and followers, you must have five skills—without which, even those with a high-propensity to trust will struggle to be vulnerable with you:

- Ability: Perform your role effectively and predictably. Especially in new teams, be sure to define your role quickly, or risk being judged either by a predecessor or by an unclear yardstick.

- Integrity: Share your values, and then demonstrate them with your actions. Name and keep your ethical commitments, as well as live by the shared norms of the team or organization.

- Transparency: Model openness and interpersonal risk-taking. Work in the open when possible, delegate openly, and disclose private information (e.g., your own thoughts and feelings) to others.

- Benevolence: Demonstrate a genuine care for the well-being of others. Provide loyalty, emotional support, and task support when needed.

- Kinship: Nurture an intersectional sense of belonging. Create an accepting and inclusive environment where everyone can feel a sense of belonging.

In addition, new leaders should consider the following strategies to become more trustworthy:

- Manage initial expectations. When starting with a new team, some leaders enter with a set of credentials and past experiences that raise the team’s hopes too high. For example, they might think you can fix all of their problems easily, when there are messy organizational issues and leadership conflicts outside of your immediate control. Not living up to those expectations can cause trust to plummet and cause even languishing among the team. Instead, new leaders should set sober expectations in terms of time and impact so that they can meet and eventually exceed those expectations.

- Import trust from others. While you may be new to the team, other leaders in the organization may have already built trusted relationships with your peers and reports. If you can build visible and meaningful relationships with those trusted figures, you may be perceived as more trustworthy by association.

- Be responsive. We’ve all experienced the dread that comes with the run-up to a scheduled meeting with a leader: our minds create all sorts of narratives for why they wanted to speak with us, most of them disastrous. In a world of asynchronous communication, those moments can become even more frequent, if less intense. Set reasonable expectations, but try to avoid delays that could leave new team members imagining your possible motives.

Hybrid work has its own challenges when it comes to building trust:

- Reduced cues: In person, we use cues from body language and tone to decipher trust, warmth, and attentiveness—all of which virtual tools hamper, potentially slowing the development of trust over time.

- Limited interactions: Shared spaces lead to more and varied interactions (e.g., the watercooler conversation), which help us form a fuller picture of who others are, challenging our initial stereotyped judgements. In virtual settings with only formal meetings, though, we may never see others more fully or find those commonalities that could help us extend our vulnerability.

- Inequity and division: One of the biggest unknowns of hybrid work will be whether it exacerbates an inequality of voice and visibility in the organization. Moreover, in many organizations there are already cliques and camps forming around those who choose to return full-time and those that don’t. Ultimately, this may lead to disparities in trust between teammates and leaders that could be impossible to repair.

- Novelty and confusion: Trust relies on individuals following and enforcing the team’s agreed upon norms and values, but hybrid has fewer established norms. Teammates will have different assumptions, which can lead to miscommunication and mistrust.

How to build trust in the workplace

With these challenges in mind, we recommend that all hybrid teams and their leaders:

- Begin as you mean to go on. Past research of virtual teams offers two unsettling warnings: a) If team members don’t begin with a belief in and commitment to trust, it likely won’t develop over time, and b) long-term patterns of trust or mistrust appear as early as the first few minutes of a group’s life. We encourage teams, especially temporary teams, to initially adopt a model of trust dubbed by researchers as “swift trust” that asks members to assume a basic, transactional form of trust from the get-go and then verify and adjust their vulnerability over time. Moreover, if you lead a hybrid team of any kind, you must model trustworthiness from the team’s inception.

- Eliminate values, norms, and role confusion early and often. Trust erodes with each violation of the group’s values, norms, and roles, even when those violations are by accident or caused by general confusion. Given the limitations of hybrid work, violations are more likely to occur and intent is more likely to be misconstrued. Events like team and project kickoffs should be lengthened in order to meaningfully define what’s in and out of bounds, and team and project retrospectives should be enforced to identify any growing lapses in clarity or commitments.

- Commit to responsive and robust communication. In-person communication is rarely what we’d consider to be efficient, and in that inefficiency we send all sorts of interpersonal signals that engender trust. When we shift our communication to mostly virtual tools, communication is reduced in form, streamlined in length, and even detached from the speaker themselves. Consider the one word email replies, the document that never gets followed up on, or seeing “Susan is typing” appear in Slack but no message ultimately gets sent. Distributed teams simply have to communicate clearly, quickly, and often.

- Prioritize connection. If you want trust, you can’t focus on tasks and deliverables alone. The team must spend time coming to see one another in vivid three-dimensions: finding new commonalities, demystifying differences, developing a deeper understanding of how one another thinks, and overcoming biases and divisions. This effort will require both incremental time added to formal meetings, as well as additional time reserved for less formal time together.

- Cultivate excitement and warmth. With less time physically together, hybrid teams tend to express less excitement and support. This can lead to less attraction to the group, reduced cooperation, and a decreased tendency for agreement among the team. Therefore, hybrid teams have to explicitly focus their effort on expressing excitement and enthusiasm for the team and its mission. We aren’t advocating for manufactured positivity, but rather, we encourage hybrid teams to amplify the positivity and warmth that already exists on the team. Don’t let wins and wows go wasted.

How to know if trust is increasing

Ultimately, trust is an inner choice, so it’s hard to measure, but you’ll know people are trusting you more when you see signs like:

- Reliance: Members of the team are not only willingly delegating tasks to one another, they’re not dictating how the work gets done or micromanaging. And if an individual does get stuck, they’re comfortable asking for help.

- Disclosure: Members of the team share sensitive or personal information with each other, like talking openly about one’s personal preferences, sharing thoughts and feelings, expressing interpersonal conflicts, and even admitting to failures and mistakes.

- Contact Seeking: Members of the team spend time together and building meaningful relationships (perhaps even in their free time!). Over time, they choose to stay on the same team rather than leaving the organization.

Read about how to rebuild trust in the workplace in Part II.

The Evolutionary Edge

Every Link Ever from Our Newsletter

Why Self-Organizing is So Hard

Welcome to the Era of the Empowered Employee

The Power of “What If?” and “Why Not?”

An Adaptive Approach to the Strategic Planning Process

Why Culture/Market Fit Is More Important than Product/Market Fit

Group Decision Making Model: How to Make Better Decisions as a Team