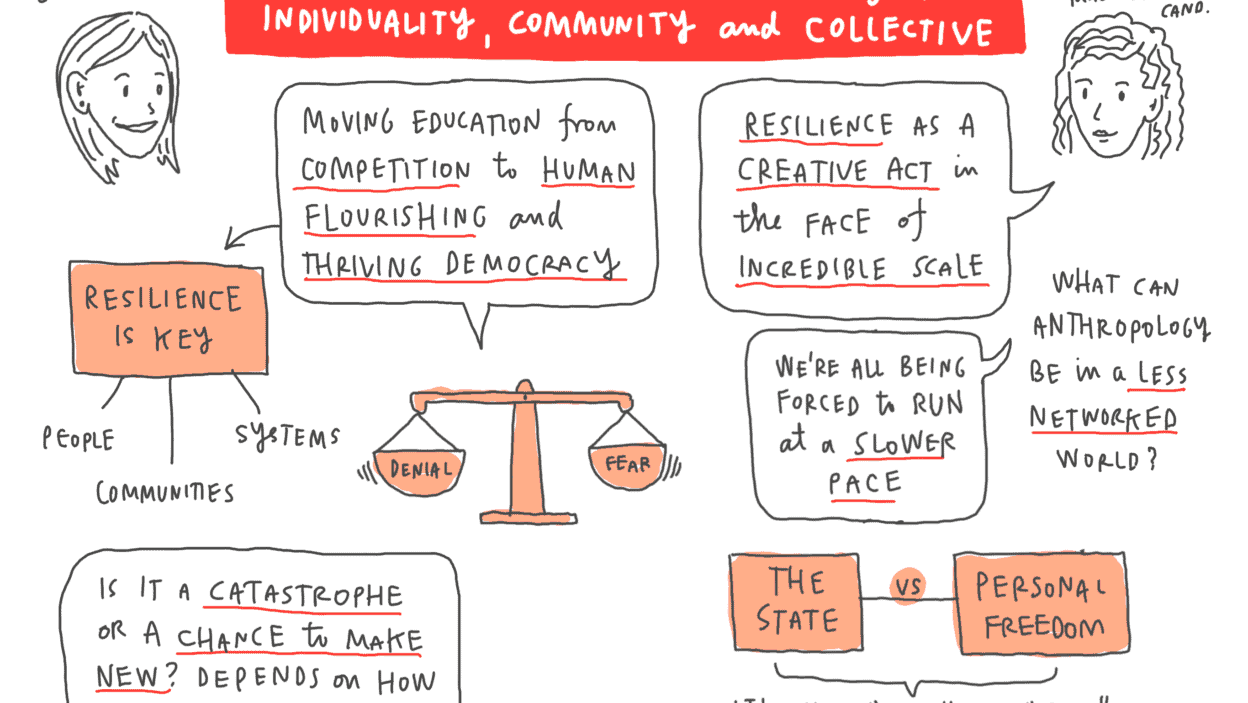

In this panel, Annie Malcolm, Ph.D. Candidates in Anthropology at UC Berkeley, and Erin Raab, Ph.D. and Co-Founder of REENVISIONED, provide their perspectives on why an academic lens is particularly relevant to our current circumstances.

Read the Transcript

Lucy Blair Chung:

Hi. Thank you all for tuning in. Erin, I just saw your video pop up and Annie, where are you? I’m looking. Oh, okay. Both of you are on. Thank you. Sarah, do we mind, can we turn off the…

Erin Raab:

Yeah.

Lucy Blair Chung:

That’d be great. Thank you. Thank you for teeing that up and Rob, thank you. And Bud, thank you. I’m not going to give a ton of background on Annie and Erin because they’re actually going to get into a bit about what their work does. But Erin has been for nearly two decades working with organizations and nonprofits around her mission around equitable world through education. She got her PhD at Stanford’s graduate school of education and she’s now the cofounder of ReEnvisioned, which is a movement to transform our schooling systems from one organized for competition, I think she’ll get into this, to one that fosters human flourishing and thriving democracy.

Erin and I have had the pleasure of working together, so that’s phenomenal. I’ve seen her in action. I think I’ve always appreciated what she has to say. I think you guys will be left with some really nice nuggets of knowledge. Then Annie happens to be my sister but also has a really interesting perspective on resilience. Annie’s a PhD candidate in anthropology at UC Berkeley. She’s currently working on wrapping up a dissertation on ethnographic field work in Wu-Tang art village and has been supported by Fulbright. I’m going to get right into it with you both. But first, how are you both? Are you both okay and are you and your loved ones healthy and well? I feel like that’s important to cover off.

Erin Raab:

Yes.

Lucy Blair Chung:

Okay.

Erin Raab:

Yeah. Thank you for starting with that.

Lucy Blair Chung:

Yeah, definitely. Where are you both calling from? I’m in Brooklyn, but Erin, you’re calling in from?

Erin Raab:

I’m right near Palo Alto, California.

Lucy Blair Chung:

And Annie?

Annie Malcomb:

I’m in Oakland, California.

Lucy Blair Chung:

Nice. Okay. First, and we had a really fun prep session, so I can’t wait to get into this and it went way longer than it should have. So we’re going to try to constrain it. What’s the major question that your work tries to answer? And then tell us how your work is connected to resilience. We’ll just start there. Erin, do you want to kick us off?

Erin Raab:

Annie can go first.

Lucy Blair Chung:

Annie works too.

Erin Raab:

Either way. Do you have a preference, Annie?

Annie Malcomb:

Go ahead Erin.

Erin Raab:

All right. I would say that my work as an academic and as a nonprofit leader, which you touched on this a little bit, but explores how to transform our schooling system so that it moves from one that incentivizes really competition, a focus on social mobility and test score growth to one that fosters these broader aims of human flourishing and a thriving democracy. This requires understanding schooling from a systems perspective as well as of course exploring what it means to flourish as a human and to thrive as a democracy. The two bodies of literature that speak to human flourishing are philosophy and social psychology. So I’ve spent a lot of time reading in those fields.

I think resilience is directly related at three different levels. First, at an individual level, resilience is really the psychological strength that allows some people to adapt and thrive faster after they occur challenges or setbacks. Since we all face hardships and loss and change in our lives, resilience is a core component of flourishing, which is something I honestly think about a lot. And it’s a skill like Rob was talking about… Bud was talking about that it’s a practice, not a trait so we can cultivate it in our lives through a number of practices like he was doing with the point and the thumbs up exercise.

I think second, our communities need to be resilient in order for individuals to flourish. It turns out resilience is as much a property of communities as it is of individuals who will show up for us in our moments of need and challenge. A community is only as strong as its social bonds. I think this is as true for a team or a company as it is for a neighborhood or a city. I think about it all the time as I’m building and managing teams.

Then third, our communities will only flourish if our systems are resilient, and this is a bit of what Rob was talking about, right? At a systems level, it turns out, and he was touching on this a little bit at the end, but that efficiency and resilience are really in tension with one another. They’re not mutually exclusive, but they are in dynamic tension. As he was talking about just-in-time manufacturing, it’s great because you don’t have the unnecessary product stored at different points along the process, but any changes in your supply chain and there’s no resilience or slack to the system. So the whole system falls down. I think about this all the time as we try and bring efficiency thinking into our schooling system and into our organizations, that efficiency pursued indiscriminately can take down a whole system.

Lucy Blair Chung:

Thank you. Annie.

Annie Malcomb:

Thank you, Erin and Lucy. I’m interested in resilience as not merely a recuperative act, but also as a creative act. Beyond addressing what gets restored in resilience, I want to ask what gets made, what becomes possible and where does resilience take us? I am an anthropologist and I study artists in China and their worlds and attunements and narratives. The pressing question in my work is about imagining a better world to come. There’s this quotation that I love from [inaudible 00:05:39] that is art places itself on the side of life. She goes on to talk about… Kind of going against catastrophic thinking.

I work just outside of Shenzhen, which as many of you know is the world’s factory. It was China’s first experiment with capitalism. It’s sometimes called China’s Silicon Valley recently, but my interlocutors want a different kind of life. They live near a mountain, they want a slower life, they want spirituality and they want simplicity. I call this collective resilience in the face of the fast pace of urban life. Shenzhen is a city of millions that was built out of a village of only thousands in only 40 years. If we think about scale, and I think coronavirus really forces us to rethink scale, Shenzhen is exceptional and it’s intense to grow that much in that amount of time.

Taking seriously the conditions of post-socialism as the context for my research in China, I want to think resilience as a collective endeavor. My friends in China have remarked recently on WeChat, which we can talk about, that nationalism has made their response to coronavirus so quick and effective. I would love to get outside an evaluation of the state as good or bad and think about and dialogue about what different political structures afford in terms of response to crisis.

I think of China as a system of adaptation to change. A person in their seventies in China has experienced the communist revolution, the founding of the People’s Republic of China, the great famine that killed an estimated 45 million people, the cultural revolution, market reform and opening up, capitalism, unprecedented economic boom, industrialization, and then becoming the world’s superpower and now this, Wuhan, and then becoming the first place to flatten the curve.

I’ll just add my answer to this question with a couple of thoughts about my work and on a more personal level. A lot of the things that happen in my work have become really relevant in living in and thinking through this moment. Anthropology has always been remote work. Classically, the anthropologist arrives on the beach with all his gear and there’s not another white man in sight. He’s far from home and he can even become strange to himself as he studies this strange culture. Field work is also a waiting game. It’s unglamorous and it involves many days waiting inside and maybe even ill from infections that you didn’t grow up developing the antibodies to fight.

Lucy Blair Chung:

Thank you both for that. I think that’s just important context on both of your backgrounds and the connection to it. I think if I’m an attendee right now, I’m sort of thinking, well these two kind of feel different from the other speakers today. An academic lens. Why bring in an academic lens? We did take an interdisciplinary approach today. We’ve had yoga teachers and movement experts as well as some of the kind of executives at various organizations. But one of the things that both of you kind of probed me on during our prep session was what do you mean by an academic lens? Can we help you define that? I think I’d love to hear from each of you on what is an academic lens and why is an academic lens so important given what we’re facing right now?

Erin Raab:

Annie, I’ll let you go and take the first one on this one.

Annie Malcomb:

Yeah. What is an academic lens? It’s a question I resisted a bit, but an academic lens is systematic so it can take something concrete and empirical and make meaning. We often think that thinking systematically is about looking at data, but an academic lens can be more holistic. Specific things are part of bigger patterns. So how can we make meaning of the specific things that are happening right now? In my area, an academic lens is also qualitative. So it goes beyond numbers and statistics into other aspects of societal phenomenon. Feeling, texture, space, experience, narrative, rhythms, daily life, ordinary things, ugly things. We seem to have endless statistics about what’s happening, but do we have an emotional understanding or humanitarian approach to what’s happening? Your kid’s at your feet instead of in school, your partner suddenly running the finances of a startup in the living room and the lady in your Zoom yoga class who doesn’t know that everybody can see her changing her pants in the middle of the class.

An academic lens also slows the breaks because it’s knowledge production, not profit production. Right now we’re all being forced to slow down the way that we participate in the economic system and an academic lens in large part, and we can argue this point, is not about producing profit, which takes place at a prescribed timescale, but about producing knowledge, which is hopefully universal, lasting, boundless. This critical distance that takes place outside of profit driven systems can offer space. It can be capacious. I think maybe we can find some relief in that capaciousness right now. We may need that.

Lucy Blair Chung:

Thanks. Erin, what about you? Then I think we’ll get into some questions because there’s interesting ones coming in. Definitely start populating the questions. We were running a little late too, so I’m trying to make up a bit of time. Yeah, there’s some good questions coming in. So yeah, Erin, take it away with what is the academic lens and why ?

Erin Raab:

I think I’m going to overlap a lot with Annie, so I’ll try and go quickly. But I think that right now on the one hand we have a lot of people not taking this epidemic very seriously. They’re continuing to go out and party and not really thinking about how it affects them. On the other hand, we’re also dealing with a lot of fear and that this just exacerbates the many cognitive biases we already have as humans that keep us from rationality, good judgment, accurate assessment of risk. Fear is driven by the amygdala in the brain, our fight or flight center, and it makes our rational brain much less functional.

I think an academic lens can be helpful in a couple of ways. As Annie was talking about, it’s systematic and I think data driven in a positive way but with an eye towards the ways that data can deceive. I think one of the biggest things I got out of my PhD was thinking about statistics and the different ways that hard cold facts can actually misrepresent reality. I think we’re extrapolating from really flawed data right now because we just simply don’t have good data right now. That’s creating a lot of fear. I think that academic lens, we go deep and we try and gather all the information and as Annie was talking about, that stories as well as statistics, it’s understanding the human element as well as thinking about the systems. That it considers it from multiple perspectives and domains.

I read everything I could find on the biology, the epidemiology, the social, the political, the economic. All of these different lenses matter and need to be put in conversation with one another. I think that that’s something that academics and academia is uniquely poised to do. I think to Annie’s point about knowledge production, it’s knowledge production, but hopefully that matters for us in terms of making meaning, assessing risk and designing and creating a better future. The idea is to analyze and synthesize and be able to actually inform how we go forward. Of course this is dependent on academics themselves not being amygdala hijacked and then just rationalizing and whatever information they can find which happens because hashtag academics are humans too. I think it’s important to remember that that’s out there.

Lucy Blair Chung:

Thank you both. Okay,. we’ll get into some questions. I think now it can be a bit more conversational. “What is the value of making meaning from data statistics and from the virus?” That’s from Gregory. Then he kind of added on and said, “How is sense-making related to meaning making?”

Erin Raab:

We haven’t decided anything about how we’ll both approach questions. So I think we’ll just jump in.

Lucy Blair Chung:

There are particular questions about China that I think will be geared towards you. So Erin, if you want to take this one first and then of course, Annie, if you have a build, feel free to weigh in.

Erin Raab:

Yeah. Every time that we are interpreting evidence or data, it can be lots of things. Whether it’s statistics or story, we are making meaning. We are as humans meaning makers by nature. We’re creating narratives all the time and trying to make sense of our world. The value of making meaning from data is that we need to be able to both ourselves and as a society assess risk and make decisions so it wouldn’t be good. Gavin Newsome has just put a shelter in place in order across all of California asking people to stay home. Partly because of the data he’s getting that suggests this is going to overwhelm the health care system.

On the other hand, I have a lot of friends who are very, very scared about this virus and the data would suggest that for any particular individual, it’s unlikely to be particularly dangerous unless you have underlying conditions. I’m not trying to minimize the danger of this. I think this is very, very serious and real. But I think that being able to look at the data that we have and being able to make good decisions either as a leader or as an individual and assess for us is really, really important. I think to what Annie was saying about being able to create new visions and create out of this is that we can make meaning. There is no… We can catastrophize this and we can think about it as the end of everything, or we can think about it as an opportunity to create something new and both are equally true and possible. It’ll depend on how we as individuals and as a community decide to make meaning out of it.

Lucy Blair Chung:

Annie, this one for you from Jackie, “I’d be interested to hear more about the folks in China who said their socialist government helped their systemic response to the pandemic.” I think you touched on this a little bit, but it’d be interesting just to hear given your field work and your experience there, what you make of that.

Annie Malcomb:

Yeah, I mean I think in the west we get a lot of true stories about the difference between having personal freedom here and having personal freedom in China. I think what a lot of my friends have been saying is, “Well, it’s different here.” I’ve been saying, “How did you deal with this? What happened and how did you feel safe and how did you know what to do?” And they said, “Well, it’s different here.” I mean for better or worse nationalism, especially that nationalism that has been really cultivated in the last few years in the Xi Jinping era, which is particularly centralized and that has its real dangers. And that kind of governmentality can create a more centralized message that gets out to people quicker and that also gets taken more seriously and people just have a different relationship with evaluating the risk in violating personal freedom versus violating a message from the state. I think we just think about those things really differently from our context.

I would love to think of these things outside of, “That’s bad,” or “That’s good,” and “We have democracy so that’s better.” Into a more, “Okay, what did that allow the government to do? What did that allow? How quickly did that allow hospitals to make new beds, to treat people in Wuhan? How quickly did that allow a shelter in place or quarantine order to take true effect to truly find the curve?” Yeah. People aren’t celebrating nationalism. My friends aren’t saying, “This is so amazing.” But they’re just saying this is the reality of what just happened in our last few months.

Lucy Blair Chung:

That feels like a good segue. They’ll take one more question. “Considering facts don’t change behavior, how do you balance academic facts with reality stories?” I feel like as researchers, this is interesting as well. Maybe let’s tie it to, how do we balance academic facts about resilience, whether it’s collective or individual with the reality stories of really what resilience, how it actually plays out? Erin, you want to take this one?

Erin Raab:

Okay. Sorry, it switched where I thought that question was going. Can you re state the question [inaudible 00:19:29] about resilience?

Lucy Blair Chung:

Sure, sure. How do you balance academic facts about resilience? I’m sort of shifting it to make sure we stand by that. How do you balance academic facts about resilience and what you’ve studied and the objective pieces with the reality and of course your own personal experience with resilience and how it actually plays out?

Erin Raab:

Yeah, that’s great. I’m going to speak to an individual level. I think we could talk about this on the community or the societal level as well. I think that what social psychology has given us is a lot of facts about how people who are resilient practice resilience in their lives and there are a number of really concrete strategies. In preparation for this, I started writing a piece to be like, “What are the 10 concrete research backed strategies that would build resilience in your life?” But while statistics wouldn’t help with that, I think we often learn from stories of people and how they put it into practice. While social psychologists have collected lots of data on how this works on average across populations and in groups and for individuals, that’s been turned into ways of learning about how to build that in your own life.

For instance, one of them would be that we’ve learned a lot about how physiologically moments of connection help us release oxytocin, dopamine and improve vagal tone, which regulates heartbeat. We’ve got lots of data on this, but that’s not helpful until you start learning about how to build good connections and you hear stories about, for instance, even the Italian people singing on the balconies or you start thinking about what does it mean to build connection in my own life? How do I create space and time to be having valuable conversations and in depth conversations to listen deeply to the people around me? How do I think about contributing? Until you get kind of the stories about how people put into practice, it’s hard to take it and adapt it for your own life. But I think that’s one of the ways that we move between the science and the data and stories for behavior change.

Lucy Blair Chung:

Thank you so much, Erin, and thank you, Annie. We’re going to go to the next. I think Sarah is going to come back on. Thank you both. You can log your videos.

Erin Raab:

Thank you.

The Evolutionary Edge

Every Link Ever from Our Newsletter

Why Self-Organizing is So Hard

Welcome to the Era of the Empowered Employee

The Power of “What If?” and “Why Not?”

An Adaptive Approach to the Strategic Planning Process

Why Culture/Market Fit Is More Important than Product/Market Fit

Group Decision Making Model: How to Make Better Decisions as a Team