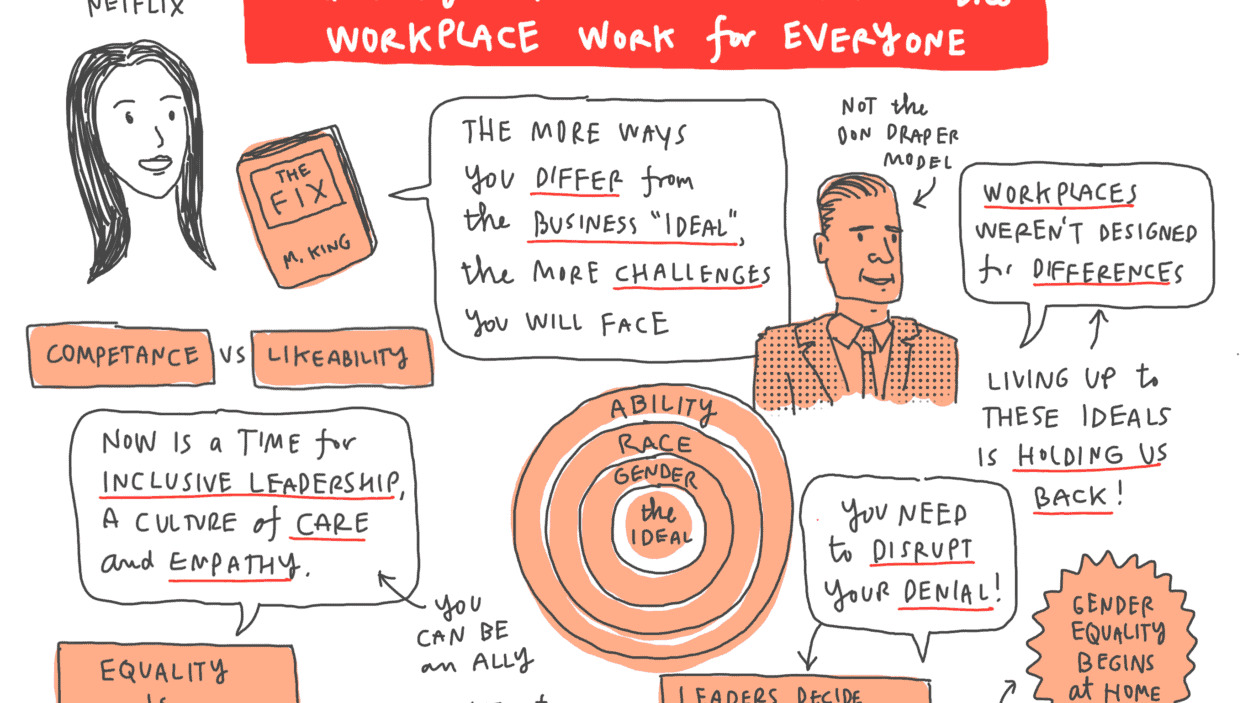

The transition to working from home is already revealing some surprising assumptions about gender roles and labor divisions. Michelle P. King, Director of Inclusion at Netflix, highlighted why men and women still face inequality at work and home, and what everyone can do about it:

- The “standard” hurts everyone. The “ideal” leader and employee is still based off of a stereotype—think Don Draper—and employees that fail to meet that stereotype face an uphill battle. But it’s important to note: this impacts women as well as men.

- Keep an eye out for differences. The workplace isn’t “designed for differences”—and as leaders, it’s often all too easy to overlook barriers. To create an environment where more people can succeed, it’s up to us to call out and fight back against the “standard.”

- Share the load at home. Especially with all activities taking place within the home, have conversations and determine the best way to divide up the labor at home. Only by addressing the full workload can we move towards true equality.

Read the Transcript

Michelle P. King:

Thank you. Thank you so much. It’s such a privilege to be here so thank you to everybody for giving me your time. You know, when I started my work about five years ago one of the first conferences I actually shared some of this with, I thought it was just going to be a small conference in America because I got invited to speak, I had just finished my research, and I agreed to go along. It was in Pennsylvania. I had just moved to America so I didn’t even know where Pennsylvania was. I was like, “Sure. I’ll go along and speak.”

I turn up at the conference and it happened to be America’s largest conference for women. There was about 15,000 attendees. Michelle Obama was speaking that year. I was really nervous anyway because I was sharing research that was kind of counter-intuitive and countered the dominant narrative out there, which was that we don’t need to fix women, we need to fix workplaces. I’ll go into that in a minute.

I turn up and was really, really nervous because most of the dominant thinking at the time was sort of around Lean In and this idea that women need to do more and be more to fit into established world of work that doesn’t really value them and their capabilities in the same way it does men.

It was really challenging to get up there and present these findings. I was really nervous. Anyway, when I did I finished my talk and I noticed a lot of women started out with pens and pads in their hand taking notes of all the actions they need to take and they slowly put it to one side because it wasn’t that sort of talk.

When I finished I came off stage and there was a young woman who came up to me and she was quite red in the face and she had tears in her eyes. I was like, “Oh goodness. What have I done?” This woman comes up to me, puts both her hands on my shoulders and she says, “I want you to know I’m going to stick up on my wall what you said.” I was like, “What did I say?” She said, “That I don’t need to be fixed. That I’m good enough just as I am.”

It was in that moment that I realized I really needed to share the story. That’s what started this journey about four or five years ago of writing this book, which is called The Fix. It’s about the barriers that exist in workplaces for men and for women because of gender and equality and how that really plays out differently for all women.

The book really takes you through the 17 barriers women face, the six that men face. I don’t know. They’re very odd numbers but that’s really trying to clarify the most number of barriers you’re likely to encounter over the three phases of your career if you’re a woman because women’s careers unfold differently from men’s.

The book really walks you through that but, importantly, why it is that inequality exists in workplaces because most of the people watching this might not even be able to explain how inequality functions in different organizations. You know, what is the problem that we’re trying to solve for.

Importantly, when you understand how it works it makes it a lot easier to solve it. Very quickly for a lot of people that are listening, gender and equality specifically in workplaces but it comes across in all forms of discrimination is actually pretty simple. How it works is in organizations most companies are designed with an ideal worker in mind and that tends to be the Don Draper, if you’ve watched Mad Men. It’s a 1950s white, middle class, heterosexual, able-bodied male.

Importantly, that’s also somebody who is willing to engage in dominant, assertive, aggressive, competitive and even exclusionary behaviors to get ahead. It’s someone who is willing to make work the number one priority. That sort of standard came about in the 1950s and it’s really sort of since organizations were designed. It’s seen as this ideal.

Research has been done to date to show that this ideal is pretty much embedded in most organizations even today. When you think of a manager or a leader you’re going to think of not only a male but this ideal standard.

The problem is the more ways you differ from this ideal standard, the more barriers you’re likely to encounter in your workplace because organizations weren’t designed for different. They were designed for people who most closely fit this ideal standard.

Likewise, the more ways and more similarities you have in common with the ideal prototype or a standard Don, the easier it is for you to advance, right? Because you have your similarity in common with the ideal.

The challenge, though, in my research and something that surprised me was that I thought the standard worked for men and so I always say that I feel like I owe all men an apology because when I was writing my book I was writing it for women and it didn’t occur to me that actually the standard doesn’t work for men. I spent a lot of time researching and talking to and studying the challenges that this whole system of having this ideal creates for men. We can go into some of the barriers a bit later on in terms of the challenges that men encounter.

But what creates entire workplace inequality is when you have this ideal, leaders sort of most closely fit the ideal and they engage in behaviors that encourages employees to also engage in those behaviors, which all mirror Don, and so you have workplace culture and entire organizations … In fact, it’s why most organizations function in the same way that really replicate the Don Draper prototype.

What’s really interesting, for me, is when we think about the challenges we’re encountering now and something my book also touches on, which is the future world of work and a lot of the transformative changes that are coming our way. You know, in order to best prepare for the future world of work and even some of the challenges we’re experiencing now, which mirror those that we’re likely to encounter in the next five to 10 years due to things like AI, robotics, and nanotechnology, we need workplace cultures that accommodate difference and can value that difference and harness it.

We need different types of behaviors. We need a lot of empathy, a lot of collaboration, a lot of collective problem solving, a lot of creativity and innovation. When you think about the types of environments that facilitate that, that’s really cultures of equality.

Great study by Accenture shows in cultures of equality, which are really environments where you feel like you belong, you feel like your identities are recognized and you feel valued for that, you’re six times more likely to innovate. Also, in those environments women are six times more likely to advance and men are twice as likely to advance to senior leadership positions.

You might say, “Well, Michelle, why is that? How can everybody be more likely to advance?” That’s because we’re no longer advancing a small number of people that fit the Don Draper ideal, right? Everybody has got an opportunity to make it.

When we think about this sort of environment, we think about those challenges people are encountering, what keeps this whole system in place, the reason we haven’t solved this, even though we know what the challenges are and we’ve been at this for a long time in the diversity and inclusion space, it’s because of something I discovered through my own research, which is called gender denial.

It’s this idea that we deny differences, we deny different experiences of workplaces and as a result we deny an equality. There’s this assumption that workplaces are meritocracies, that they function for everybody in the same way and they don’t. The reality is workplaces weren’t designed for difference and success does discriminate and it discriminates based on how closely we fit that ideal standard.

Men and women face tremendous pressure to try and live up to that standard and it comes at a major cost to our confidence, to our self-esteem but also to our ability to navigate work and home life. A lot of people I imagine have encountered this right now. Their companies are still putting pressure on employees to dress a certain way when they do VCs, to hide their children, to not talk about the fact that right now it’s impossible to manage work and home life perfectly, right?

All of that hiding, all of that trying to fit in is to try and live up to this ideal. It creates tremendous challenges. My work and through the book I’ve really tried to highlight all the challenges that this ideal creates. Just quickly, before we go to the Q&A I just want to touch on one example of one of the barriers that’s very common and affects both men and women. Just to give you a sense of the kinds of challenges the book encounters.

For women, early on in their careers one of the very first barriers they’ll encounter is something called the Conformity Bind whereby you have to live up to the Don Draper ideal to be seen as competent in workplaces because that’s the standard for what good looks like, right? You’ve got to engage in this behaviors and try and fit that ideal standard.

When you do that as a woman you’re sort of trading off the standard that society holds for what good looks like for women, which is being more meek, mild, unassuming, caring, sort of more maternal characteristics. Women can do that, live up to that feminine standard but they’ll be seen as competent but not likable. Then they live up to the Don Draper standard and they’re seen as competent but not likable.

You’re trading off likability for competence and it can create a lot of challenges for women because likability is really important when it comes to promotions but so is appearing competent and living up to that Don Draper ideal.

Women face this almost impossible standard in terms of how to behave at work and we can get into how that’s different for all women because something I’m really passionate about is how many challenges and how this is compounded by all the areas of difference.

When we think about race and ethnicity and gendered racism and how that plays out and how much harder it is for black women in particular to try and fit the Don Draper ideal because white women have their whiteness in common with Don so while it’s hard for them, it’s still easier for them compared to black women at work who don’t have that in common with Don and have to face all sorts of gendered racism throughout their careers with things like the angry black woman stereotype or microaggressions. It’s much harder as we layer in difference and so my book talks to that as well.

There are a few things all of us can do and I just want to leave you with that before we jump into the Q&A. Think about your previous speaker, I think awareness is the key. I think all of us can disrupt our denial and become aware of how our workplaces aren’t designed for difference, to really think about the privilege we’re given by fitting the prototype and the challenges that creates for other people and really confronting that. You know, I’m a white woman and I think about my white privilege a lot and how having that in common with Don makes it easier for me.

You know, I think we can also start to really try and understand what the barriers are and how they work differently for everybody, right? Understanding the barriers men face, understanding the barriers women of color face. Because when you have that awareness and understanding it allows you to be an ally, it allows you to take action, to make equality a practice.

That might be speaking up, advocating for your colleagues, calling out inequality moments when your boss makes a comment to a parent on the call on your next VC around, “Why can’t you just keep the kids quiet?” You can step in and be an ally and say, “Hey, it’s a really difficult time. People don’t have childcare. Consider the whole person.”

I think right now demonstrating empathy and care for one another and really thinking through how we can support one another is critical. I’ll just stop there because I really do want to answer all the Q&A but I just wanted to share that I think right now the challenge we’re in requires inclusive leadership, it requires a culture of equality, it requires a culture of care and that is really what my whole book is about. I’m really excited at this time to be able to share that with everybody.

Sarah Dickinson:

Yeah. A deep, deep thank you. Rest assured, the excitement is shared by our attendees as well. Tons of questions and plus ones and fans in the chat here. I’m going to pick a couple of choice questions.

“I’m curious how you’re incorporating gender expansiveness and trans and gender nonconforming inclusivity into your work. Many companies are struggling with this.”

Michelle P. King:

Yeah. It’s very challenging, particularly when I’m talking about it in a very gender binary way, right? I’m talking about Don and I’m talking about … For me, there’s a difference between men and women so gender identity versus masculinity and femininity and how that plays out in prototypes in organizations, right? I think it’s important to acknowledge this.

My main point around it and why I think it matters is because what we’re actually asking for when it comes to equality is freedom. For me, equality is freedom. When I use equality I use that word very intentionally and it’s about freedom. It’s the freedom to be yourself at work and to be valued for that.

Right now in organizations we are handcuffed. Inequality, gender inequality specifically is handcuffed. We’re handcuffed to behaving like Don to be seen as effective regardless of your gender identity or your orientation. You are handcuffed to conform to that because that is what good looks like in organizations.

For women, society then handcuffs us to engaging in more feminine behaviors to be likable. For me, the same is true for men. Something like the femininity stigma is incredibly challenging for men. Men are handcuffed to conform to Don and when they step outside of that and display behaviors that are more empathetic, more collaborative, more communal, which are behaviors typically associated with women, they are seen as … They’re penalized. They’re seen as less effective, less career-oriented, less ambitious, and so there are tons of studies that show that.

I mean, even men who reduce their work hours for family reasons are penalized more than women in terms of pay after controlling the sort of usual factors that affect pay. Men face a 26% reduction in pay on average compared to women who face a 23% reduction. That’s how much we are bound to these standards.

For me, this is very much about freedom and how do we give employees freedom to show up? You know, there might be times where being more masculine and assertive and dominant in those stereotypical masculine ways are required, right? But there might also be times where we need to display more stereotypically feminine attributes. It’s just giving people the freedom to respond to their environment in the most appropriate way, which, by the way, we need now more than ever.

Sarah Dickinson:

Exactly.

Michelle P. King:

We need that freedom, right?

Sarah Dickinson:

Yeah. I mean, just riffing a little bit on to today and the current context within which we find ourselves. “What are the rituals for inclusive company cultures?” I’ll get that tongue twister right. “What are some rituals that inclusive cultures can adapt during the current situation?”

Michelle P. King:

I think there’s a few things. I always start with leaders. My book pretty aggressively holds leaders accountable. The reason for that is leaders determine … They’re in a position of privilege, right? They get to decide every day how you’re going to experience the organization. They decide what behaviors get accepted, rewarded, endorsed, ignored. They really are the culture in many ways because they set the standards for those behaviors and they also role model the behaviors that they want.

It’s really important for us to acknowledge that leaders drive culture through their behaviors, right? And through the way in which they lead. For me, the first thing I say to all leaders is they have to disrupt their denial. My research has shown that a lot of very senior leaders are simply in denial or unaware, right? Because you’re in a position of privilege so it’s seen as, “I don’t have to do anything.”

I think the ultimate privilege is really being able to solve inequality that you, yourself never have to experience and every leader has that opportunity. For me, this is really an invitation for leaders to lead and they can do that by really managing the moments.

Culture and inequality in these terms can sound quite ambiguous but they’re not. This is your lived experience of the workplace, right? Day to day interactions, behaviors, exchanges. That’s where culture gets made. What we’re really asking leaders to do is do the work yourself in terms of educating yourself on the barriers.

Read my book, understand the challenges women are likely to encounter, the challenges men are likely to encounter, and when those moments happen or play out in your workplace, lead. You know, manage those moments. When somebody excludes somebody or … I’ve got hundreds of examples in my book of different ways that this shows up or when somebody, which is a real thing that happened to me, when a male colleague tells you to wash the dishes because you’re the only woman on the team.

You know, that’s your opportunity as a leader to step in and to manage that moment and to call it out and use it as an opportunity to learn. I think that’s what we’re asking leaders to do. Simply put, just do that one thing, manage the moments and to do that, well, you’ve got to know what they are. Do the work to recognize them for when they show up.

Sarah Dickinson:

Incredible. I think Netflix probably more than many companies an example of empowerment, of setting some very simple rules that others are interpreting. There’s great freedom I’ve seen in terms of creating that culture. You know, shared very, very generously out there as well.

I’m going to do one last question because there are lots more but I’m going to do one more. It’s another timely one. “The Atlantic had an article this week suggesting that the mass quarantine will set women back in their gender roles due to lost income, working from home, children at home, what have you. What’s your perspective on that?”

Michelle P. King:

Equality begins at home. I get this all the time about … I get asked this question and it’s a hard question to answer. I’m a gender equality advocate. For me, solving this is reverse engineering it myself in workplaces.

Ultimately, the inequality that we experience at work is because of inequality in society, right? My book I give a bit of the history on this and how it plays out but the fact that we don’t value men and women in the same way, all their contributions in the same way, is a societal issue and we have this at home where women tend to carry an undue burden of all the invisible work associated with domestic and childcare responsibilities.

We also just have it in the way that we value men and women’s careers differently. Studies show this as well. The interesting thing is, again, an assumption in that that the system works for men and it doesn’t. Studies that I’ve looked at and the men that I’ve researched as part of my PHD it’s shown that actually this creates tremendous pressure for men to live up to this breadwinner image and to not be associated with activities at home as well.

You know, men, unfortunately, have this situation where their whole identity around being a man is tied up with Don. When men lose their jobs or they lose that breadwinner status or they drift away from it by taking on my childcare responsibilities, like before, the femininity , the challenges that creates, it not only disrupts their sense of identity around who they are at work but it disrupts your identity in terms of who they are as a man. It’s a double whammy.

I talk a lot in my book about how do we shift from being breadwinners, that idea, to bread sharers? How do we unpack the load? One action that everybody can take, and it’s something that works really well, is to actually try and make the invisible visible. It’s to really try and keep a … I know it sounds really practical but it works. Keep a list of what the activities are in your house and make sure that’s shared.

Importantly, my friend Eve Rodsky wrote a book called Fair Play, which talks about this issue. Based on her research it’s not actually necessarily divvying up the load completely equally. That’s not the case. If you have 10 items on your to-do list it’s not saying, “You take five, I take five.” It’s actually taking your items that you have and seeing them through from start to finish. That’s actually the most effective thing.

Something that really irritates me is when I’ll get to the dishwasher and the dishes are next to the dishwasher but not inside, right? Or we’ll have the laundry on top of the basket but not inside. We need to see this through. That’s the thing is to really see it through.

Then also in my own research something I found is that there’s a double whammy where on average apparently people have 105 items on their to-do list, women in particular. That’s a lot that you’re carrying mentally. It’s very taxing. Studies also show when you’re also accountable for the social and emotional wellbeing of your children at home, so you’re the primary person every night to lie in bed and have chats with your kids and understand who they’re fighting with and who is their friend and what’s happening, when you’re carrying that and now the anxiety around coronavirus, “When can I go back to school? When can I see my friends? Why can’t I …” You know, when you’re carrying that on your own that adds an added level of stress, that becomes very unmanageable for women.

I would also say when you’re doing your to-do list think about some of the things that are completely invisible like managing the emotional and mental wellbeing and see if that’s shared equally because if it’s not simply sharing that, studies show, helps a lot with managing the load. That would be my advice for how to cope.

Sarah Dickinson:

Thank you so much, Michelle. I get the sense of the trove of information and insight that you have on all these topics is quite something. I am excited to … Not only do I want to read your book but 25 people, I feel like a game show host now, 25 people have the chance to win a copy of your book. We’ve got 25 copies. For the favorite tweets of the day we will be contacting folks who tweeted throughout the day and you get to be the lucky recipients of Michelle’s book The Fix. Feels like an incredibly important read, a very timely one. Michelle, thank you.

Michelle P. King:

Thank you so much. I appreciate everybody. Thank you.

Sarah Dickinson:

Yeah. Take good care. Bye bye.

Michelle P. King:

Bye.

The Evolutionary Edge

Every Link Ever from Our Newsletter

Why Self-Organizing is So Hard

Welcome to the Era of the Empowered Employee

The Power of “What If?” and “Why Not?”

An Adaptive Approach to the Strategic Planning Process

Why Culture/Market Fit Is More Important than Product/Market Fit

Group Decision Making Model: How to Make Better Decisions as a Team