Jim Barksdale, the former CEO of Netscape, is famous for his mantra, “all new opportunities start out looking like snakes”—in other words, all new opportunities first present themselves as threats. But in business, unlike with snakes, the choices are rarely a binary “fight or flight.” Discerning what to do when presented with an opportunity is itself another classification challenge: there are times when well-worn “best practices” may serve you, and others when they’ll leave you snakebitten.

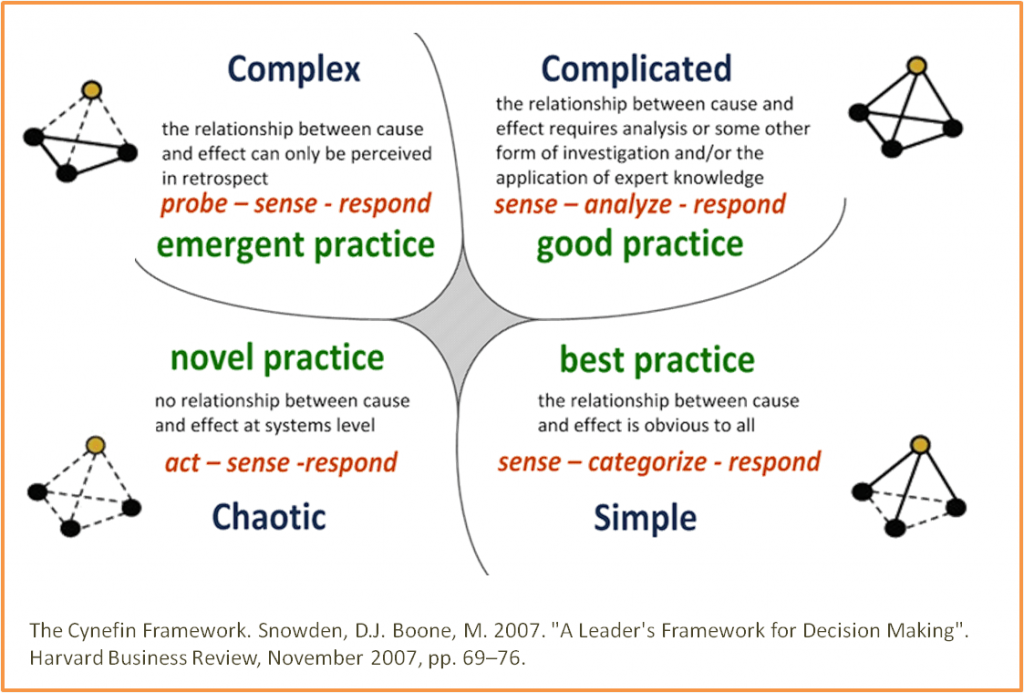

The Cynefin (pronounced “kuh-NEV-in,” Welsh for “habitat”) Framework, created by Dave Snowden and Mary E. Boone, is a helpful model for classifying the context you’re experiencing, and what the appropriate response may be. The model delineates five contexts for decision-making and action: simple, complicated, complex, chaotic, and finally, disorder (or unknown).

According to the authors, these contexts are broken down as follows:

- Simple (the known). In this context, cause and effect are obvious to all observers, and solutions typically take the form of best practices. Think of repetitive business practices like expense reports or quality control: input is received, assessed and categorized, and the “best practice” is applied (e.g., “Accept or Reject”). Little discernment is required, making these processes easy to automate or delegate. Here, leaders can largely focus their efforts on the continuous improvement of their practices and processes.

- Complicated (the knowable). This is typically the domain of experts and “good practices,” in which the link between cause and effect is not immediately clear, requiring some investigation. Moreover, while there are definitely wrong approaches in this context, a variety of responses can achieve a beneficial result. For instance, in order to negotiate a partnership agreement, you may hire a lawyer who, after study, offers you a discrete series of choices to select from. Here, leaders should identify the issue, analyze potential solutions using their expertise (or outside experts) as a guide, and respond accordingly.

- Complex (the unknowable). In this context, the connection between cause and effect is unknown and indirect, and may evolve over time. This is true of most markets today: customer demands shift, new competitors arise, new technologies emerge. Trying to plan ahead can seem futile when it’s unclear what will happen in six months as the “Four C’s” of uncertainty run rampant. That’s why experimentation is so critical, and why our approach to Strategic Planning—Adaptive Planning—asks teams to make “bets”: hypotheses that they’ll test to determine the best approach forward, iterating as new information arises. This results in “emergent practice,” and requires leaders to adopt a philosophy of rapid learning.

- Chaotic (the incoherent). Here cause and effect are constantly shifting, and there’s simply no point in planning. Most teams experienced this first-hand at the beginning of the pandemic when switching to remote work practically overnight. In this context, the best thing to do is act first, then evaluate whether or not it worked.

- Disorder (the indeterminable). This is when the context you’re facing doesn’t appear to fall into any of the previous categories. Once again, the best response here is action, probing the environment to see what environment you’re in.

While we find that Snowden and Boone’s model neatly describes the different contexts that organizations might find themselves in, it’s not so easy to discern the context you’re in when you’re actually in the thick of it. As we’ve worked with clients and grown our own business, we’ve noticed the following biases and maladaptive patterns creep in:

- Viewing all problems as simple. Some leaders—especially experienced and successful ones—simply believe that “there is nothing new under the sun.” These leaders may scoff at new trends or novel competitors and stick to the playbook that has already brought them success, believing that perceived changes or uncertainties are overblown. These leaders may be right at times, but eventually, every playbook becomes outdated, and their overconfidence blinds them to coming disruption.

- Viewing all problems as complex. Particularly in creative fields, we see leaders who view all business processes through the lens of the complex—even repetitive and routine tasks with clear “best practices.” These organizations miss out on obvious and easy process improvements that can free up their teams’ time to focus their experimentation where it matters most. Yes, an organization might find itself in an uncertain context, but not every problem within its walls is a complex one.

- Developing an over-reliance on experts. Some leaders have never seen a problem that couldn’t be outsourced to a consultant. These leaders typically mistake a complex context for a complicated one; assuming that with enough time and expertise, a single “perfect” solution can be divined. These leaders eventually end up with reams of immaculate plans and little action to show for it. Unfortunately, as the saying goes, “No one ever got fired for hiring McKinsey,” so their behavior often continues unchecked until a true existential crisis—one demanding action and not more plans—emerges.

- Defaulting to a “wait and see” approach. In some chaotic or disordered contexts—where events unfold quickly and return to some form of normalcy—taking no action is often the best course of action. Unfortunately, some leaders then take away the lesson to always wait and see, delaying critical decisions until the last possible moment, hoping that the situation will go away. Meanwhile, they prevent their team from accessing the resources they need to test and learn their way into new solutions.

- Defaulting to a “firefighting” approach. Solving problems in a chaotic context can often feel heroic and elicit effusive praise from the rest of the organization. Over time, these rewards can create a culture of “fire drills,” where reactivity becomes the norm, and the organization becomes incapable of long-term planning and investing.

Ultimately, leadership requires both situational awareness (knowing what’s happening around you) and self-awareness (knowing what’s happening inside you). With practice and reflection, organizations can get better at identifying what’s a snake, what’s a deceptive-looking log, and what might just be a new trail to an unexpected opportunity.

The Evolutionary Edge

Every Link Ever from Our Newsletter

Why Self-Organizing is So Hard

Welcome to the Era of the Empowered Employee

The Power of “What If?” and “Why Not?”

An Adaptive Approach to the Strategic Planning Process

Why Culture/Market Fit Is More Important than Product/Market Fit

Group Decision Making Model: How to Make Better Decisions as a Team